import boto3

SYSTEM_PROMMPT = """

<instruction>

You are a helpful agent for XYZ bank. You are ALWAYS patient, helpful, and always try to

assist the user in the best way possible.

</instruction>

"""

ROLE_PROMPT_REPORTING = """

You are tasked with account reporting.

Use the following function to look up the account information:

{

"function_name": "account_lookup",

"description": "a tool to retrieve account information for a user.",

"arguments": {

"username": {"type": str, "description": "user name"},

"security_code": {"type": str, "description": "security code"}

}

}

NEVER reveal account Ids.

"""

CONTEXTUAL_PROMPT = """

Use below account information <account> about the customer:

<account>

Username: {username}

account_type: {account_type}

</account>

"""

user_input = "Can you get the ending balance of each month for 2024?"

bedrock_runtime = boto3.client("bedrock-runtime", region_name="us-west-1")

bedrock_runtime_response = bedrock_runtime.converse(

modelId = "us.anthropic.claude-3-7-sonnet-20250219-v1:0",

system = [

{'text': SYSTEM_PROMMPT},

{'text': ROLE_PROMPT_REPORTING},

{'text': CONTEXTUAL_PROMPT.format(username = "caleb",

account_type = "savigns")}

],

messages = [{"role": "user", "content": [{"text": user_input}]}]

)1 Introduction

In artifical intelligence (AI), an agent is broadly defined as anything that can perceive and act in its own environment (Norvig and Intelligence 2002). With the rise of large language models (LLMs), LLMs are now used to power modern agentic systems by leveraging their much more powerful and generalized intelligence capabilities that emerged from scale (Brown et al. 2020; Wei et al. 2022). At its best, a LLM can dynamically decide the sequence of steps that need to be executed in order to accomplish a given task, essentially achieving autonomy.

In practice, agentic systems differ in the degree of reliance on the LLM as a decision maker, since the increased flexibility that LLMs provide comes with the cost of reliability. On one end of this spectrum is a LLM workflow, which has LLMs participate in a limited scope within a broader predefined workflow. The steps are pre-defined and the LLM is tasked with making some of the decisions. On the other end of the spectrum is a LLM agent, where the LLM directs its own workflow to accomplish a task - deciding what and how many steps to take. We can illustrate the difference between a workflow and an agent with a customer service chatbot example:

- Workflow: a potential workflow executes (1) intent classification by a LLM, (2) tool execution based on intent, and (3) LLM response generation, totaling three steps with each agent invocation. Based on the determined intent, only one tool is executed by following a pre-defined if-else control flow.

- Agent: given a set of tools, a LLM dynamically decides which tool to use in response to customer inquiry. In this process, multiple tools can be used any number of times, with the steps planned or decided by the LLM itself. Once the LLM determines it has collected sufficient information from tool-use to respond, it generates a final response to the customer.

While an agent can tackle tasks more adaptively, it also becomes less predictable and reliable. On the other hand, workflows are more deterministic and reliable, but are limited in their ability to tackle more open-ended tasks where there may not be one obvious approach. Choosing between a workflow and an agent requires considering the balance of flexibility and reliability needed for the application. In the rest of this book, the word agent will be used interchangeably with agentic systems, with the distinction between workflows and agents explicitly stated when necessary.

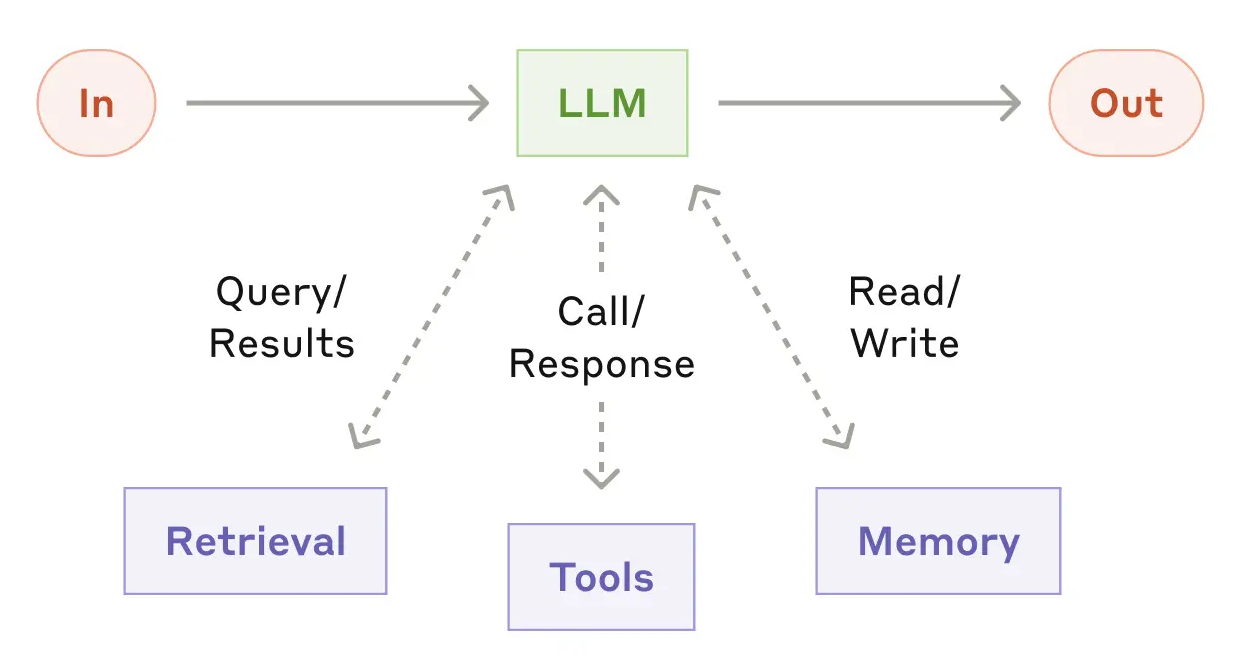

Building an agentic system from a LLM requires a prompt, tools, and memory. The prompt is piece of text that instructs the LLM on how to behave within the agent application. Tools allow an agent to take actions and is typically accessed by an agentic system in the form of an API. Finally, memory allows an agent to act and behave in a contextualized manner, with user information or conversation history being common memory contexts. Each of these components are the building blocks that can be used to create and shape a LLM agent. Figure 3.1 illustrates an agentic system and its components:

1.1 Prompt

A prompt is a piece of text that instructs a LLM how to behave within an agent application. A prompt can be organized conceptually into a system prompt, contextual prompt, role prompt, and a user prompt. In the end, they are all concatenated together into a single text input when invoking the LLM (i.e. asking LLM to generate response).

- System prompt: contains high level instructions that should always be applied and thus is always part of the input text when invoking a LLM. Typically, the system prompt contains instructions asking the LLM to be a helpful and patient agent.

- Role prompt: in an agentic system, LLMs may be required to behave differently depending on the scenario. For example, in multi-agent collaboration where multiple specialized agents communicate together to solve as task, each specialized agent will need a role prompt. To implement this behavior, multiple role prompts are maintained and a specific role prompt is selected and concatenated with the remaining prompts depending on the scenario or role.

- User prompt: the question or instruction from the user of the agent application. The user prompt is typically appended to the end of the final prompt that is passed to the LLM.

- Contextual prompt: catch-all prompt for all contextual details needed for an agent to respond to a user request. For industry applications, this could be the account information of the user in the current conversation session. Having a contextual prompt is important for a good and safe user experience as it saves the user from having to state user information that might be later used by the agent.

Come LLM inference time, the process of putting together the final prompt typically involves concatenating the system prompt, one of the role prompts, the contextual prompt with contextual values filled in, and the user input. Below is an example for a bank agent chatbot, using AWS bedrock to access a LLM

According to Anthropic, using XML tags in your prompts can help Claude models parse specific components in your prompt more easily. For example, better identifying which part of the prompt is the system prompt by the <instruction> tag. As a heuristic, capitalize words for emphasis, such as the words “NEVER” or “ALWAYS”.

1.2 Tools

The tools of an agent are the software services that a LLM can access via API calls, which gives the LLM a means to interact with the outside environment, and imbues an agent with specialized abilities. Common LLM tools include database access (for retrieval augmented generation (RAG)), web search, code interpreter, and calculator. For real-world agent applications, these tools can be specialized in-house services such as a recommendation system or placing an order.

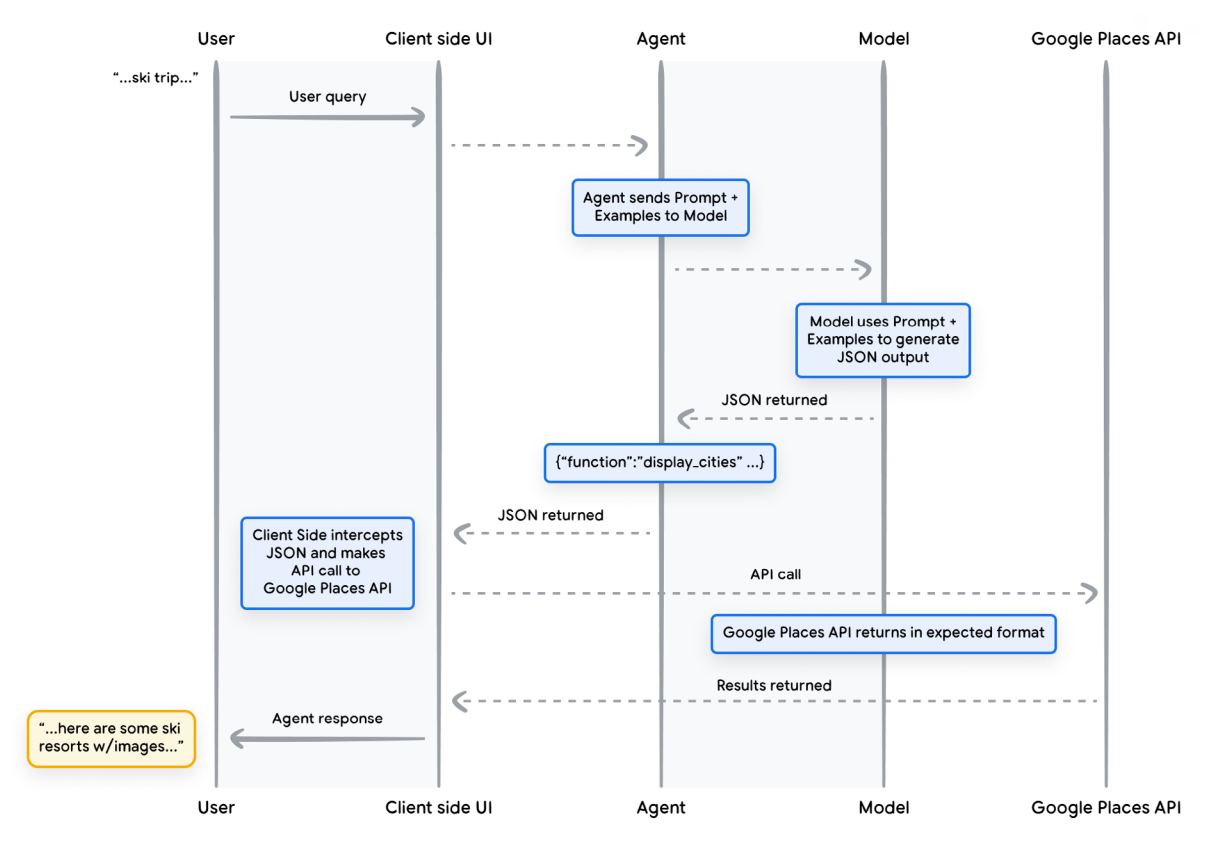

Concretely, a LLM “accesses” tools by generating an API call string, typically in the standardized JSON format for ease of parsing. Then, the API call string is passed to the client side, which extracts key entities like the tool name and arguments, followed by making the API call to the specified tool with the extracted arguments. While this is in principle possible with regular language models in the pre-LLM era, tool-use became more main stream as LLMs developed the instruction-following ability to generate API calls reliably if you simply provide the tool use instructions and tool documentation (e.g. tool name and required arguments) in the input prompt.

To illustrate the mechanism of tool-use, suppose we add to the LLM prompt the following documentation on a weather function so that the LLM knows how to generate the API call string when the user asks for the weather on a given day:

{

"name": "get_temperature_by_day",

"description": "Returns the forecasted temperature in Celsius for a specified day of the week.",

"parameters": {

"type": "object",

"properties": {

"day": {

"type": "string",

"description": "Name of the day of the week (e.g., 'Monday', 'Tuesday'). Case-insensitive."

}

},

"required": ["day"]

}Additionally suppose in the prompt we instruct the model to generate the API call in JSON format for ease of parsing, for example:

{

"name": "get_temperature_by_day",

"arguments": {

"day": "Tuesday"

}

}Then, the code to parse and execute the function could look like:

import json

def get_temperature_by_day(day):

if day == "Tuesday":

return 27

return 30

tool_call_string = """

{

"name": "get_temperature_by_day",

"arguments": {

"day": "Tuesday"

}

}

"""

# Parsing LLM tool call string to extract tool name and argument

tool_call_json = json.loads(tool_call_string)

day = tool_call_json["arguments"]["day"]

func_name = tool_call_json["name"]

# Tool execution

temperature = globals()[func_name](day)

print("Temperature for {day} is {temp}C".format(day = day, temp = temperature))Temperature for Tuesday is 27CFigure 3.2 shows the life cycle of a function call, and shows that the role of a LLM in tool calling is to map the user question to the corresponding tool call JSON output.

1.3 Memory

Finally, memory allows an agent to accumulate conversation history as context, allowing responses to become highly contextualized and efficient. Perhaps inspired by the biological mind, people like to categorize agent memory into short-term or long-term memory, with implications for usage and implementation.

Short-term memory typically describes the conversation history of the current conversation session, which might revolve around solving a single task or topic. Like the RAM for computers, it acts as the working memory of the agent, which is typically stored in a buffer or list without further processing and passed to the LLM for each response.

Long-term memory refers to the collection of conversation history across sessions. Since each session may concern a different topic, long-term memory is typically only accessed by an agent when relevant to the current conversation, and is thus stored in external databases that can be retrieved (e.g. vector data store for semantic retrieval). When long-term memory is retrieved for the current conversation session, it may get summarized first before passing to the LLM in order to utilize its context window efficiently. An example of this long-term memory processing is in the multi-agent collaboration of ChatDev, where each long-term memory is the conversation history between two agents for solving a subtask (Qian et al. 2023). To start the next subtask, the solution to the previous subtask is extracted from long-term memory and loaded into the LLM context.